View from Academia: In the Time of the Coronavirus, We Need to Kill Recycling

By Dr. William Oliver Hedgepeth, American Public University

We need to kill recycling. Replacing recycling is becoming one of the key logistics challenges today. At least it is in parts of Europe, and maybe in the U.S. Will this logistics challenge happen in the U.S.? Will it happen within 10 years?

U.S. waste management services appear to be defined by two kinds of applications: waste items and recycled items. They are the products we purchase from retail stores and manufacturing entities and use in our homes, offices, schools, outings, and vacations.

What Is Waste and What Are Recycled Items?

We have human-made hills rising around our cities with connecting roads expanded to accommodate a growing stream of trucks full of waste from local and out-of-state sources. We view those products of waste management systems as playing a part in today’s logistics challenge.

Other more current examples of items that are not considered part of the recycling effort include:

• Foods and liquids

• Electric cords

• Water hoses

• Chains

• Plastic bags

• Styrofoam

• Large sections of wood

• Plastics

• Metals

• Furniture

• Stoves

• Washing machines

What about cardboard? It seems that cardboard and paper are part of the limited number of recyclable items for the recycle trucks that visit our homes several times a month. Also, you can recycle cat food cans or any cans of human food items, but only after you wash out their food and liquid residue.

Plastic water bottles are recycled, but not their plastic caps. They go in the waste container.

What Is Really Not Waste?

At your home, how many old laptops are stashed away? Or do you still have mobile phones, cameras, movie projectors, hats, shoes, furniture, books, clocks, lamps, or even manual or electric typewriters? These items may be a piece of our personal history and as such, are headed not to either the waste container or the recycling container.

How long has it been since those stashed-away items were used? Are they only a year old due to closing an office in 2020 or items from a small trucking company that went bankrupt and closed in 2010? Do you have items that are 30 years old because they were your mom’s? Or are there 70-year-old rusty hand tools from grandpa? Or maybe, it’s furniture from four past moves that you are saving just in case your children get married and need furniture.

Our new normal forward-looking business strategy needs to be based on rethinking the boundaries and rewards gained from recycling and waste management. So do we kill recycling or kill waste mountains?

The Limits to Recycling

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines recycling as “the process of collecting and processing materials that would otherwise be thrown away as trash and turning them into new products. Recycling can benefit your community and the environment.”

Before the coronavirus pandemic, recycling was a big business and a part of everyday homes and offices. This year, however, COVID-19 is affecting recycling for retail and manufacturing businesses and is most likely to impact the EPA approach to recycling.

This impact is partially due to recycling centers across America stopping collections because of the possibility those items could be contaminating workers with COVID-19. In fact, some recycling centers are experiencing a shortage of workers who fear exposure to COVID-19.

An example of recycled items is plastic materials, which include bottles, containers, bags, and film product wraps. That EPA definition includes an important future planning phrase for recycled materials, “turning them into new products.” How does this happen? Those recycled materials could be reused, repaired, remanufactured, and refurbished.

Reusing a product is a problem to some people when it is put back on the shelf for purchase. To repair is to find and fix it and then put it back on the shelf for purchase.

Remanufacture is more labor-intensive. It may mean taking the item apart, throwing away worn or broken parts, and remaking it as a product for purchase.

Refurbishing is usually thought of as furniture that is sent off to a company where it is repaired or reupholstered and polished to be receptive to a new customer’s needs.

Note that this list of “re” actions does not include recycling. Recycling is more than an application. Separating recycling from all these other “re” terms is the logistics challenge many of us face. Maybe it’s a retailer’s nightmare more than a challenge.

What is this nightmare? It is the nightmare of massive numbers of returns due to the “new normal” purchasing habits spawned by online shopping in this pandemic environment.

Customers are shopping online more in 2020 and with no cost returns, buying and returning is a common practice. Global online shopping for the remainder of 2020 is expected to reach a market size of 4 trillion, with 69% of Americans expected to shop online. And millions of items are yet to be returned.

The Circular Economy of Reverse Logistics

Reverse logistics and recycling are part of a complex business cycle. Waste items can be a straight line or liner economic model, starting from raw materials, made into a product that is sold, and then used until it becomes a waste item, as shown in Figure 1.

That product you just purchased, such as a pair of shoes or a new car, started with dozens to thousands of kinds of raw materials from all over the world. These raw materials are brought together in a manufacturing plant. From there, logistics and supply chains take over and place the product in a retail store for purchase. Once that product has served its purpose, it most likely goes into the trash can.

Figure 1: Linear Economic Model. Image courtesy of W.O. Hedgepeth.

That linear model of building an item and disposing of it when no longer needed is considered simple to understand. From this linear economic model, we expand to a circular economic model, which focuses on the redesign of the product, not just sending it to waste or recycling. Going from linear to circular involves a concept of complexity.

However, a circular economic model may have many overlapping parts. As a complex system, a circular economy brings into the discussion a diversity of subjects like human behavior, forest ecosystems, biology, social science, how we think about innovation, and many other areas linked together.

The circular economic (CE) model examines all the raw materials used in that linear model to make a product, like a pair of shoes, and provides a study of the qualitative and quantitative parts of those resources. Each of those raw materials is examined for the value it contributes to the manufacture of that final product; it also considers how none of that raw material should go to waste. Consider that 100% of each raw material source – metals, glass, plastics, leather, or whatever – should not be wasted.

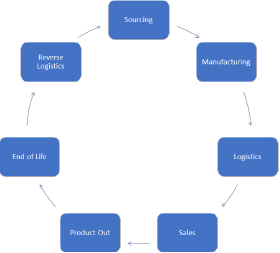

A circular economy is described in Figure 2. Starting with the sourcing of the raw materials, we move to manufacturing, logistics, marketing and sales, product out, end of life proposal, reverse logistics, and back to sourcing.

Figure 2: The circular economic model from sourcing back to sourcing. Image courtesy of W.O. Hedgepeth.

This concept and the manufacturing processes impact many aspects of how raw materials are produced or mined and improve not only business but the environment too. The concept of economic growth is part of this complexity of understanding the scope and range of CE in work and in our life.

Thus, CE is taking reverse logistics out of the dark side that is so easily defined as waste. As Dell Technologies says, “Every year, humanity uses more natural resources than the earth can regenerate. Our circular design approach aims to eliminate the concept of waste by continually reusing resources.”

The Circular Economy in the US

The concept of CE is not new. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce produced a report in January 2020 focusing on CE events in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River region. This report documented how a CE approach to materials such as water, energy, steel, plastics, pulp, and paper can save billions of dollars and significantly reduce greenhouse gases.

The circular economy is a bridge to possible environmental, financial, and product savings, and it minimizes waste. But this CE concept, the complex model, is also a flow of data that is captured from building a product to end of life disposal. It is a data item tracking the inventory movement of that product. So not only is the product important, but the data, data tracking, and handling problems are now more important for the forward flow of data up and down the supply stream as shown in Figure 2.

Leading Forward to the Next Best Ideas for Recycling

We need to design a new normal for reverse logistics and circular economy. Customer service and reverse logistics are linked.

But there are many questions to be considered about replacing what is more common in the two applications of waste items and recycled items. The following questions are the basis for further research and operational planning:

- Replacing recycling is the logistics challenge? When will the logistics challenge happen? In 10 years? Less?

|

- What is the customer service challenge?

|

- How do we get products from their place of origin?

|

- What is the customer service challenge?

|

- What is the role of reverse logistics in the circular economy?

|

- Where do you put reverse logistics in a company?

|

- What is the reverse last mile?

|

- What are the issues in shipping hazardous materials?

|

- How do we get products from the customer?

|

- What is the “time to fail” for a product?

|

- How can we support designing for circularity?

|

- What rules are we facing with circular economy and reverse logistics?

|

- How can we support recycling and reusing?

|

- How do we predict the inventory of reverse logistics and the circular economy world?

|

- How can you support extending the lifetime of products?

|

- What affects these “new initiatives” in the circular economy?

|

- Who can take back everything they sell?

|

- Is the 2020 pandemic driving or slowing circular economy or reverse logistics?

|

- Can we change from a loss center to a profit center?

|

- How do we change from a linear economy to a circular economy?

|

- How do you get consumers to engage in the circular economy? The conversation about reverse logistics needs to change.

|

- What is the next impossibility?

|

The reuse and recovery of a product in the CE cycle as shown in Figure 2 are more important than simply the linear model of recycling as shown in Figure 1. The circular economy is not about reducing waste. It is about doing good and less harm. The circular economy is about designing a model in which waste is not considered as a byproduct of reuse or recovery.

Article originally published 12/15/2020 at https://apuedge.com/in-the-time-of-the-coronavirus-we-need-to-kill-recycling

Dr. William Oliver Hedgepeth

Dr. William Oliver HedgepethDr. Oliver Hedgepeth is a full-time professor at the university. He was program director of three academic programs: Reverse Logistics Management, Transportation and Logistics Management and Government Contracting. He was Chair of the Logistics Department at the University of Alaska Anchorage. Dr. Hedgepeth was the founding Director of the Army’s Artificial Intelligence Center for Logistics from 1985 to 1990, Fort Lee, Virginia.