Sustainability Initiatives for Reverse Logistics: Good for the Planet, Good for Your Business

By Robyn Kahn Federman, Liquidity Services

From the C-suite through the supply chain, increased emphasis on sustainability, spearheaded by consumers – particularly Generation Z (the generation born between 1997 and 2012) — is leading to a renewed interest in developing sustainability initiatives specifically for reverse logistics.

Consumers tend to buy from sustainability-focused companies. Sustainability is a key consideration because it essentially minimizes the environmental footprint while maximizing economic and social benefits. And it is a natural fit for reverse logistics, because the aim of reverse logistics is to recover value from returned products, reduce waste, and minimize environmental impact.

The journey to become more sustainable through recycling, refurbishment, and remanufacture extends not only through the supply chain, but throughout a company’s logistics operations and even into its HR (human resources) department -- the fair and ethical treatment of its workers is as much a part of a company’s sustainability quotient as is its use of energy-efficient fleet vehicles.

With respect to reverse logistics, what exactly are “sustainability initiatives”? How do you measure their impact? Which initiatives truly move the needle and which simply look good in a company’s ESG report? It helps to start by understanding the “circular economy” and how it impacts us in our daily operations.

What is the circular economy?

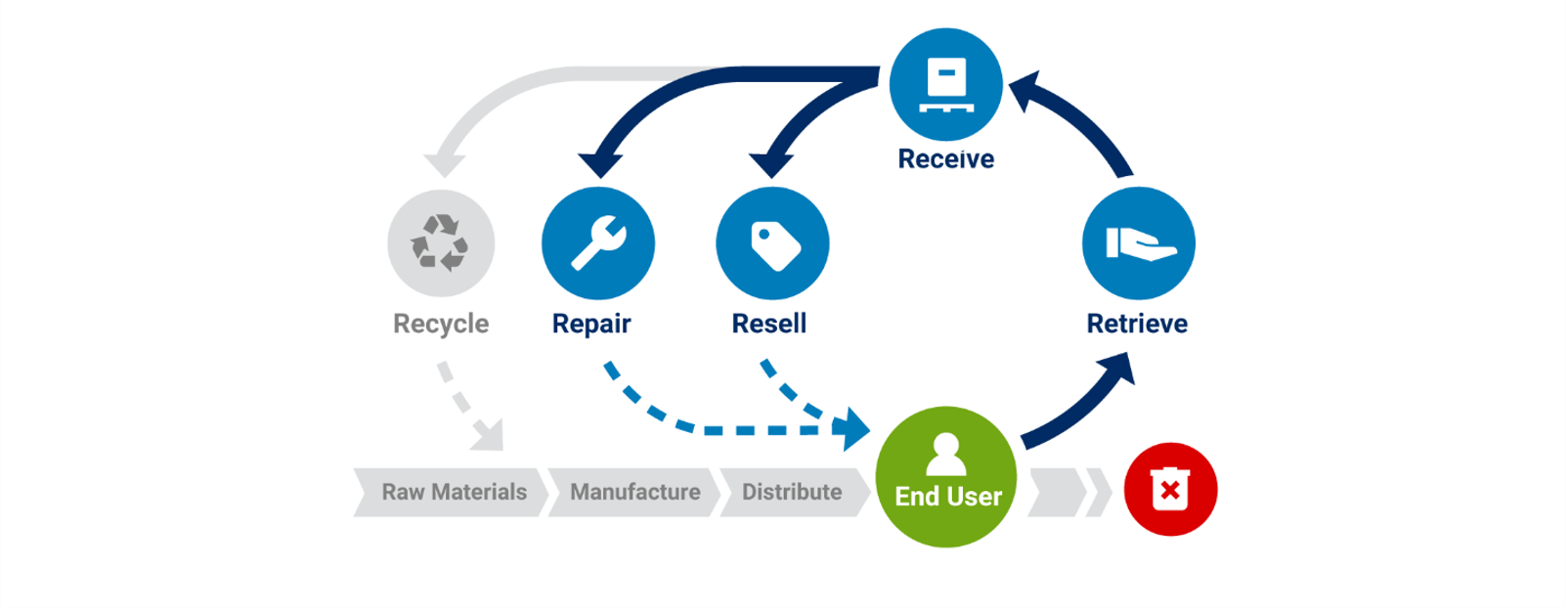

The European Parliament describes the circular economy as “A model of production and consumption, which involves sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible. In this way, the life cycle of products is extended.”

Unlike the traditional, linear process of manufacturing an item to be used and ultimately discarded, the circular economy focuses on extending the utility of assets through smarter product design and secondary marketplaces. Incorporating circularity into the economic process can save usable goods from landfills and incineration.

Retail returns and sustainability

Today, the liquidation market is worth an estimated $644 billion. Not surprisingly, driving this market is the problem of retail returns. I won’t beat a dead horse, but we all know the math: Online purchases average a 21% return rate, resulting in billions of dollars of lost revenue.

Every year, U.S. returns generate:

- 5.8 billion pounds of landfill waste

- 16 million tons of carbon dioxide

- $761 billion in lost sales

Source: Coresight Research Sustainability Insight Report The Hidden Costs of Retail Returns, 2021

Unfortunately, many major retailers are ill-equipped to handle massive return volumes. As a result, they often resort to landfilling or incinerating waste to offset the losses incurred from transporting, sorting, and storing returns versus putting usable goods on the liquidation market. This practice has a devastating environmental impact.

How did we get here?

In the early nineties, The Council of Logistics Management (CLM) defined sustainability as “the role of logistics in recycling, waste disposal, and management of hazardous materials; a broader perspective includes all relating to logistics activities carried out in source reduction, recycling, substitution, reuse of materials and disposal.”

Redesigning the supply chain to effectively handle product returns is critical for efficient remanufacture, recycling, or waste disposal.

In an efficient supply chain, management of the reverse flow can reveal some interesting resources. In addition to the obvious beginning point of the product return itself, which involves the voluntary behavior of the consumer, the company must identify the destination of the returned product – for example, the production, distribution, and reassembly lines.

Due to the diversity of products in the reverse flow, processes can involve reutilization, repair, renovation, reprocessing, cannibalization, or recycling (Thierry et al., 1995).

What can you do with a product return?

- Reuse

- Repair

- Refurbish/upgrade

- Remanufacture

- Cannibalize

- Incinerate and/or landfill

- Donate

There may be direct reuse, where some of the returned product can be reused without further production processes other than slight cleaning or small repairs. This process would include the pallets, containers, bottles, or boxes that the products travel on.

Products can also be returned by the customer to be repaired and received back in working order, where the retailer fixes or replaces any broken parts. In refurbishment, returned products are disassembled into modules, inspected, fixed, and/or replaced. In addition, upgrading the products’ technology can be considered a type of refurbishment, resulting in improved product quality.

In remanufacturing, returned products are carefully inspected and disassembled, and broken or outdated parts are replaced. At the end of the process, the result is also increased quality standards.

There is also cannibalization, which recovers limited parts of used products that are reused in other reverse logistics activities. And there is recycling, which reuses the material in the production of new parts.

Last, there is Incineration and landfilling, which should be the very last resort because of the limited capacity of waste yards and the airborne release of pollutants.

Some companies also donate, which keeps product out of the landfill and is good for the company’s public image but does not produce revenue (other than a potential tax write-off).

In reverse logistics, the types of products determine the types of logistics practices. Reused packaging, old computer equipment, unsold commercial goods, spare parts, and packaging materials are all treated differently, adding to the complexity of deciding which kinds of sustainability initiatives are practical.

There’s always a practical reason why retailers choose a particular recovery action: profit, outside forces, or social pressure. The key drivers tend to be economics, legislation, and corporate citizenship.

- Economics: Economic benefits translate to direct or indirect gains. Direct gains would include the decreased use of raw materials and waste, obtaining valuable spare parts, and financial opportunities such as the secondhand market. Customers impose strong pressure on retailers to consider environmental aspects, so retailers who are environmentally friendly about production and waste disposal will benefit. Overhauled products can be used as spares or sold on secondary markets. Even if there is no immediate measurable impact, companies are expected to be green by society and the government. A “green” image is an important element in marketing and customer relationship strategies. In a competitive environment such as retail, companies may be obliged to explore new options for take-back and recovery to better meet consumer expectations. There may also be competition drivers where the purpose is to prevent other retailers from entering the market.

- Legislation: Some countries enforce environmental legislation and charge manufacturers with responsibility for the whole product life cycle. Thus, they must consider both current laws and the possible effect of future legislation in their strategic planning. The legislation driver means any laws dictating that a company must recover its products or take them back, thus holding the company responsible for the entire product life cycle.

- Corporate citizenship: This refers to the set of values or principles that an organization holds about reverse logistics operations. Better customer services such as increasing the level of customer awareness for returning and refunding options produces better customer experiences which positively impact a retailer’s image and improves the bottom line.

Reverse logistics initiatives: myth vs. reality

Given these drivers, what specific sustainability initiatives apply to reverse logistics? There are primarily five:

- Closed-Loop Supply Chains: Closed-loop supply chains involve the recovery and reuse of materials and products versus disposing of them. This includes refurbishment, remanufacturing, and recycling. By adopting closed-loop supply chains, companies can reduce waste and minimize their environmental footprint.

- Green Transportation: This type of transportation can include the use of electric or hybrid vehicles as well as alternative transportation methods such as rail or barge. By using more sustainable transportation options, companies can reduce their carbon footprint and contribute to a more sustainable supply chain.

- Product Design: Sustainable product design can play a role in reverse logistics. By designing products with end-of-life considerations in mind, companies can make it easier to recover and reuse materials at the end of their useful life. This includes designing products for disassembly as well as using more sustainable materials and manufacturing processes.

- Collaborative Networks: By working with other companies and stakeholders, companies can share resources and expertise, reducing the overall environmental impact of their reverse logistics processes.

- Data Analytics: By analyzing data related to returns, product quality, and environmental impact, companies can identify areas for improvement and implement more sustainable practices.

Liquidity Services Inc., one of the most trusted providers of solutions to manage, value, and sell excess inventory in the circular economy, recently commissioned Elastic Solutions, Inc. (April 2023) to learn more about the reverse logistics practices of the top Fortune 100 retailers. Among the questions we asked was, “What specific sustainability goals or initiatives do you have for your reverse logistics operation?”

Fully 59% indicated that using green/clean energy was their top sustainability initiative. In second place, at 40%, was recycling. Interestingly, only 29% indicated that keeping product out of the landfill was a top priority. (Note that respondents could select more than one answer.)

Given the emphasis that the C-suite tends to place on sustainable initiatives, we were surprised that keeping product out of the landfill did not rank higher. This observation leads us to wonder whether there may be a disconnect between corporate mandates and the managers in the trenches responsible for carrying out those initiatives. Anecdotally, we still hear plenty of stories about companies dumping or burning their excess, and corporate initiatives that don’t translate into measurable practices for reverse logistics management.

The benchmarking study asked retailers a number of other questions about their reverse logistics practices, such as the average number of touches (the number of times a returned product is handled before reaching its final disposition), the average number of transportation legs (the number of times a returned product is transported until it reaches its final disposition), plans to improve efficiency, expectations for recovery, storage plans, network optimization, and more. To receive a digital copy of the full study, click https://liquidityservices.com/benchmarking/.

In search of the highest Total Recovery Value: Nirvana

A significant underpinning of the benchmarking study was the ability of retailers to apply the principle of Total Recovery Value to their sustainability initiatives.

Most reverse logistics operations focus primarily on improving recovery — not sustainability. However, by focusing on sustainability, retailers will improve recovery. An emphasis on Total Recovery Value – the full reverse logistics spectrum combining resale price with savings on handling, transportation, and storage—contributes to sustainability by producing less waste and fewer greenhouse gases (GSGs). It is good for business, good for public perception, good for the environment, good for the planet, and good for the people charged with its implementation. To learn more, visit Retail - Liquidity Services.

Robyn Kahn Federman

Robyn Kahn FedermanRobyn Federman is a senior demand generation manager at Liquidity Services, Inc. (NASDAQ: LQDT), where she develops marketing and key account programs to support the growth of the retail division. She has directed marketing initiatives for a variety of business-to-business agencies and corporations for more than 25 years. She holds an MS in journalism from the University of Kansas and an MS in sociology from the University of Chicago.