Introduction

The old expression “a high tide lifts every boat” is very applicable to retail shrink since the pandemic. All areas of shrink have increased, some more than other areas. For example, self-checkout (SCO) theft has increased due to “frictionless transactions”. Recently, Costco reported fraudulent use of memberships at SCOs through ‘membership sharing’ (multiple households using the same membership). This is a crucial pain point for warehouse clubs, as Costco derives as much as 80% of total net profit from membership fees. (ChainStore Age)

Sales floor shrink has increased, creating new, and dangerous, in-store issues of employee safety. Organized Retail Crime (ORC) groups are increasingly becoming more violent, and such incidents frequently make national headlines. The National Retail Federation (NRF) reports sales floor shrink at 1.61% of sales. E-Commerce shrink and fraud have greatly increased. Lastly, supply chains have recorded 1,778 incidents of theft in 2022 (CargoNet) or a 15% increase over 2021. (value was reported at $250,000,000)

Product Returns are another, sometimes overlooked, area that contains opportunity for shrink. Returns pose a unique challenge to retailers – a necessary evil of doing business. While returns of products for legitimate reasons are common, if left unchecked, this area of retail is rife for abuse and fraud. Returns have long been considered “a cost of doing business.” However, the sudden and alarming increase in total returns has caused some retailers to rewrite overall return policies, write return policies for specific product categories and even eliminate returns in some high return product categories.

We will focus on 4 key areas:

- The scope of the problem needs to be defined. What is the nature of returns today? What percentage of returns are fraudulent?

- We will consider some common methods of consumer-based return fraud.

- Review common methods/benchmarks to implement return protocols @ the return desk.

- Solutions to limit product returns and fraud

Breaking Down Returns

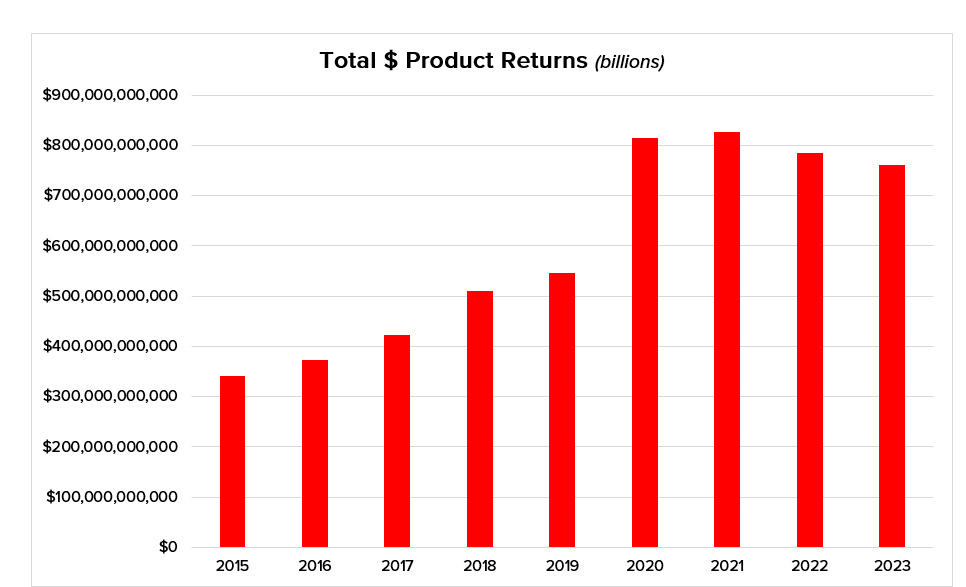

The tsunami of returns has created a huge financial concern for nearly every global retailer. Retailer returns are quickly approaching $1 trillion per year. In 2016, total consumer returns were at 8.8% of sales, growing to nearly 14.5% of sales in 2023 (SOURCE: NRF annual returns report). Over $760 billion in goods are being returned to US retailers every year (2023). Here are some facts about returns:

- In 2015 product returns were 8.8% of sales – peaked in 2022, returns now equal 14.5% of total sales.

- Product returns peaked in 2021, representing about $820,000,000,000. (this is the total sales for Walmart, Target and Home Depot combined)

The above chart tracks product returns from 2015 through 2023, and illustrates the rapid escalation of the amount of total goods being returned to retailers. As a total of US retail sales, returns now equate to $760,000,000,000 or $760 billion. By contrast, returns totaled $341 billion in 2015 (Digitalcommerce360). A large part of this growth can be directly correlated to the growth of digital sales from the pandemic. Nonetheless, returns were growing pre-pandemic, however as we enter the post-pandemic world where digital sales are returning to pre-pandemic norms, returns are remaining elevated.

How Many Returns are Fraudulent?

The basic definition of return fraud is a product that is returned to a retailer in violation of the stated return policy. Either a consumer or ORC operation has gained ‘ownership’ of a product through normal purchase, purchase from another retailer, opportunity shoplifting, tender laundering opportunity, and returned to a retailer with or without a purchase receipt.

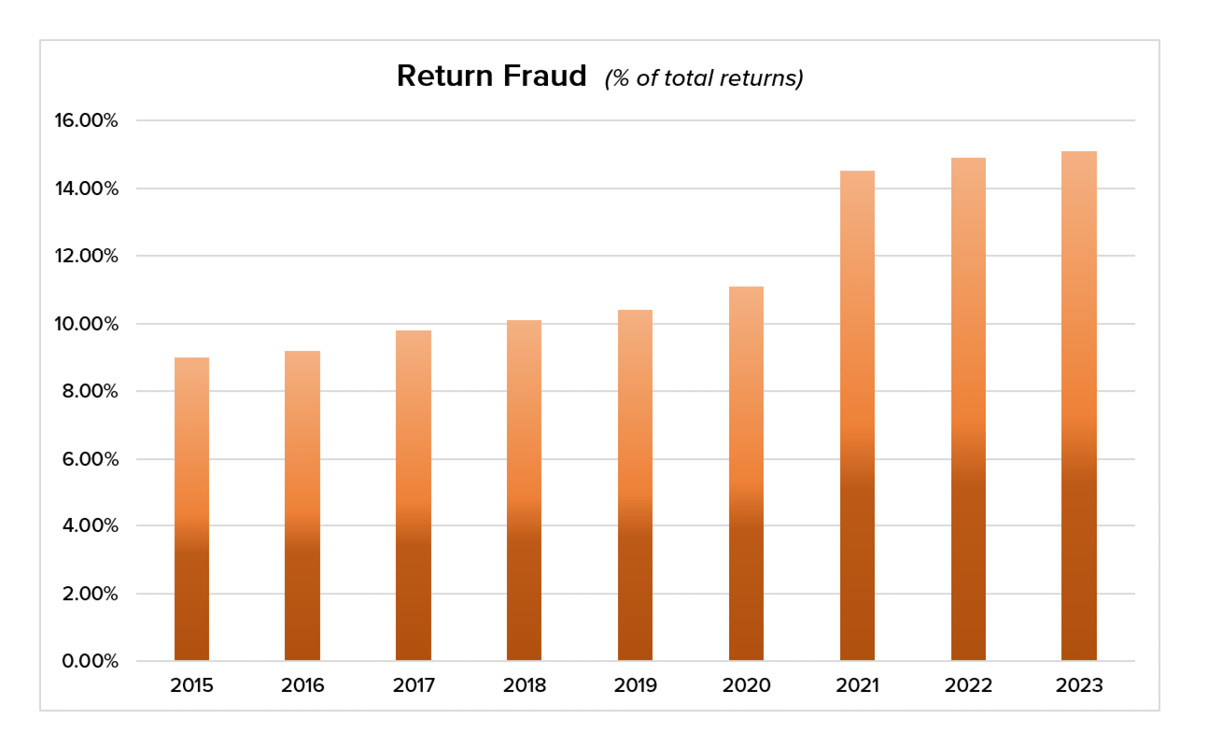

The growth of returns has brought an explosion of return fraud. Both consumers and ORC groups have exploited retailer policies and operations to return goods. These fraudulent returns have added to the growth of shrink at every US retailer. Over 14% of all returns are now fraudulent, including 1 in 5 returns without a receipt. Here are some facts about return fraud:

- Return fraud now accounts for over 14% of total returns or approximately $87,000,000,000 - this represents approximately the total revenue of Lowe’s.

- Return fraud has increased 43% since 2015 – it is one of the fastest growing areas of shrink.

Interestingly, online transactions have only increased return fraud by about 10% over traditional brick and mortar retailers. In fact, “buy online, return in-store” policies have allowed even a greater increase in both returns and return fraud than traditional retailers. Return fraud has increased over 43% since 2021 – fraud now accounts for 14% of all returns according to the latest NRF data.

As total product returns have been nearly doubling (as a % of sales) so too has the growth of return fraud. As a percentage, fraudulent returns are growing at a slower rate than total product returns, when you make the calculation into Total Dollars – return fraud dollars has more than doubled since 2015. We know the pandemic shifted consumer purchasing habits from in-store to digital, and we anticipated an equal growth in return fraud.

Beyond detecting fraud, there added incentives to monitoring returns as well. If a retailer can highlight a product with a sudden spike in returns, then they can become a greater value to their merchants by spotlighting products that may have a functionality issue that the true consumer is rejecting. Monitoring a Top 10 returned products report is an example. A manager may spot a Kids Learning Tablet that has suddenly spiked into return reports. This may indicate the learning tablet was not well built or subject to a defect. Such information can be shared with the merchant team who can then, in turn, pass the information on to the vendor.

Return Fraud Schemes

Who is committing return fraud? It is argued here that two groups are primarily responsible: consumers and ORC. Each group uses different techniques. To mount a defense against return fraud, we need to know who is responsible, and how these techniques work. Specific and targeted responses will likely prove more effective than generic and randomly applied responses.

Consumer Return Fraud

Some consumers will purchase a product and then discover the product does not work as advertised, does not fit their needs, or realize that a product is needed for a one-time use. Consumer fraud is from upright customers who end up ‘taking advantage’ of a loophole in the return policies of a particular retailer – this is why it is so important to have a well-worded, effective return policy that is enforced by the return center at retail.

- Renting (commonly referred to by fashion retailers as wardrobing) occurs when a consumer purchases a product with the intent of using it for a short time before returning it. Retailers such as Macy, Dillard’s, Nordstrom, and others, have experienced this for years. Dresses and suits are often purchased for special occasions only to be returned after the event – price tags still on many of the pieces of clothing. The advent of flat screen TV’s and other high-end electronic items (cameras as an example) have also contributed to this problem. Many consumers buy then return with the intent of a ‘lifestyle improvement’ for a short period of time.

- Returning old/damaged merchandise is when a consumer has used some product or device for a while then decides the product is old, needs to be updated, or can run better if slightly upgraded in some manner. The consumer then returns the damaged piece of merchandise that they already own in exchange for a new product. This exploit has been used by consumers for decades, whether it is the upgrade cycle of computers, computer components (commonly done in the 90’s & 2000’s), TV’s, tools, auto parts and many more product categories. This is difficult to stop unless serial number identification is used on both product and packaging. This method is very difficult to detect at high-volume return desks.

- Extending the Store Return Policy is like returning an old overdue library book without fees or damages. Retailers have always experienced consumers who buy a snow blower during winter and return it in spring. Large umbrellas, such as those sold at warehouse clubs, may be purchased in the summer, and returned in early fall, or even on a monthly basis. Consumers use this as a method of renting (noted above) but ultimately claim they took too long to return the product. Frequently, it is difficult to pin this on a legitimate, good customer and often most retailers will accept this return as an exception at the return desk.

- Bricking is common in electronics, tools, auto parts and a few other home goods categories. The practice of ‘bricking’ includes methods used to strip goods of valuable parts or upgrades and returning that new product for a full refund. For example, some consumers are known to order a new printer, remove the ink cartridges and return the product as new. Remotes for TV’s can be quickly and freely replaced as new by returning a television with the old remote. Cell phone parts can be changed out, and computer HDD (hard drives) are a commonly replaced. ‘Bricking’ also creates the age old ‘chicken & egg’ question – who is responsible for the missing parts. (more of this later in the benchmarking section)

- Open Box Fraud. Consumers always want a better price. Some will capitalize on Consumer Electronics (CE) product retailers’ policy to resell consumer returns in-store. CE retailers have long re-sold return TV’s or laptops at 10%-20% (called “open box”). One way a consumer can ensure an extra discount is to buy a new laptop, return it, then walk back in 24-48 later and save themselves $100, $150 or more. Consumer purchases a high price item and returns the product within a few days, only to have that item go to the “open box” section of the store where the consumer will buy the same unit at a cost savings of hundreds of dollars if not more – in some high-end cases even more.

ORC Return Fraud

ORC-based return fraud is much more complex and insidious than consumer return fraud. ORC has devised methods that allow them to profit heavily at the return desk of every retailer in the country. ORC will exploit the return centers of retailers who do not monitor the return area; retailers with poorly written return policies; retailers who do not monitor return exception reports, or trends and analysis of sales/return data that is SKU driven.

ORC is also more apt to use complex strategies including fake receipts, reselling, shoplifting to return for store credit (which is easily resold on the web) and shoplifting with a receipt (real or fake), all with the intent to return for credit/cash. Here are some common methods:

- Bait & Switch - returning an old smart phone in a new box or returning a box of bricks, sand, or an item of comparable weight to an online retailer. Counterfeit goods should also be considered bait & switch.

- Price Arbitrage - buying low from a retailer putting a product on sale price and returning it to a retailer that offers a higher return price. This is often done using fake, manipulated, or duplicated receipts. Examples of this growing trend include medical devices that can be purchased for discount online and returned to a brick retailer at much higher prices. This includes practices such as cross-retailer returns in which a product is purchased at one retailer and returned to a different retailer.

- BORIS - (buy online, return in store) This loophole has allowed ORC members to bring in merchandise that the store normally may not actually carry. Unfamiliarity with a product can result in products being returned past normal store policy. Pricing information may not be accurate. This is particularly problematic as online receipts are much easier to manipulate than cash register receipts.

- Employee Fraud - ORC team members will often focus on the hours a particular associate is consistently working at the return desk to allow for additional fraudulent returns to be processed.

- Tender laundering - is commonly practiced by ORC at the return desk to turn store credit into cash, store credit into another form of tender or even turn a cash, debit, credit, credit card into a total cash return.

Retailer Return Protocols or Benchmarking

Almost every product category can be exploited by a consumer or bad actor to ‘bricking’ or removing parts of the product to upgrade/update existing goods. A few classic examples of bricking include:

- Buying a home printer, removing the print cartridges and returning the printer with used cartridges or no cartridges at all.

- Buying a handbag that includes the handbag & wallet, then returning only the handbag.

- Buying a top-end PC (or notebook) then removing the big hard drive to replace a smaller hard drive from a notebook already owned. (motherboards and other products are easy to swap out in most cases)

- These are a few examples, but the list is nearly endless of parts that can be swapped out.

Considering the high-volume state at most retailers return desk (customer service), it is nearly impossible to validate every return. But is there value in implementing certain benchmarks or protocols on a basis of product category or even a random check created by prompts in the Point-of-sale system for the retailer. (modern POS systems are highly customized to nearly every retailer scenario)

More importantly, which party is financially responsible for the missing part? In the case of notebook computers, a hard drive can retail for $100-$400, if this part is removed and not checked at the return desk, where does the liability fall? The retailer in many cases either: 1) tries to resell the product, 2) sells it to a 3rd party reseller within the reverse channel, or 3) returns the product to vendor. The age-old question is who bears the cost of the missing drives, parts, or products?

To assist in mitigating these losses, can the industry set up a benchmark for all product returns? Directing store team members to have a basic number of prompts to validate a return. Using the example above, the notebook return could be validated by a POS prompt asking the associate to remove product from box, validate serial number, then finally request validation of any tamper seals that are on the product or been removed from the notebook. Similarly, a TV return process could be a series of prompts that include a prompt to confirm serial #, another prompt to ensure the remote is returned with TV and a final prompt for the power cord (all things necessary to resell the TV).

The next step is to determine which party is financially responsible for the missing or replaced part inside an expensive piece of electronic equipment? (and this goes way beyond TV remotes and HDD). This includes ultra high-end merchandise, lens and swapped parts of all types. Due to scale the retailer cannot possibly check every laptop, camera, even tamper resistant seals can be forged these days by sophisticated ORC. Perhaps someday the entire retail channel can agree on a percent allowance for missing parts or agree to a methodology to verify component level.

Who develops these return benchmarks for the entire industry? Is there a vehicle or method to distribute a benchmarking style guide to all retailers? Can this benchmark resolve all chargebacks from brand owners to retailers? These are questions that reside within the industry group Reverse Logistics Association. The RLA can be a key part of reducing returns, establishing a benchmark of returns, and building a global standard moving forward with the help of the retail community.

Solutions for the Retailer

We live in challenging yet exciting times. From a retail return perspective, the challenge is to process a growing number of returns each year. Thankfully, technology on many fronts is providing an exciting number of methods to be sure that the retailer can rightfully accept returns and minimize fraudulent returns at scale for the retailer. A quick summary of the Solution Providers that offer assistance in this area are:

- Serialization – by assigning a unique product identifier at the source can make each garment, each device, each unit trackable at the point-of-sale and the point-of-return – with or without a receipt. Incomm Product Control is the leader in this technology that can be scaled into any POS system

- Consumer identification – we all know the vast majority of shoppers are good people, however there is a segment of shoppers that do purchase with the intent to return (as discussed above) and these shoppers are trying to manipulate the point-of-return transaction. APPRIS has developed a method to ‘spot’ these shoppers that have over-used a retailer’s return policy. By using ID these shoppers can easily be identified

- Loyalty Programs – While very similar to the above consumer identification solution. An In-store Loyalty program can be leveraged as a tool for asset protection. Tracking customer returns, frequency of returns, location of the returned goods, exception reports on returns can all be very helpful in restricting returns. Best Buy, Lowes and others have successfully leveraged the loyalty program to monitor many consumer behaviors, among this observation is returns/return fraud.

- RFID enabled Point-of-Sale solutions. This is the next frontier that can protect ALL product categories and all products. Having a short-range RFID reader at POS with each item in the store tagged with next gen RFID tags can create a cloud-based database that includes the 4-part key (retailer, store #, date of purchase, tender) of when an item was purchased (or in the case of fraud – not purchased). In my humble opinion, this is the holy grail of retail. RFID POS will allow secure self-checkout in seconds, remove queues, eliminate shrink at POS (point-of-sale) and validate all returns by a unique identifier and the allowances set forth by the specific retailers.

- While not a solution provider, GS-1 and the Reverse Logistics Association are both developing new standards in barcodes that will have attributes to serialize product with a single scan and product identifier. GS-1 has developed the standard DigitalLink UPC code that will allow unique product tracking, as of this publication sunrise will be in 2025. The RLA has developed 12N codes that also can be used to track unique products with a single scan. In addition, the RLA 12N code can be used to develop benchmarked and identify if a product has been ‘tampered’ with prior to return.

The tsunami of returns has arrived as returns have increased over 30% in a short 5-year time frame – now is the time for each retailer to revise policy while remaining competitive and implement technology to reduce fraudulent returns.

Adam Hartway created a Loss Prevention solution called Point-of-Sale Activation (POSA), that, as part of the technology. that tracked & prevented fraudulent product returns. Adam has over 15 years of experience in return fraud and has worked with the Loss Prevention Research Council as co-leader of the Product Protection Work Group for 10+ years. Adam has experience working with retailers in the US, EU and suppliers in the Far East.

Justin J. Smith was born and raised in West Palm Beach, Florida. He received a Ph.D. in Criminal Justice from the University of Central Florida in Orlando in August 2022. Prior to receiving his doctorate, Justin received Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Criminal Justice, both from Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton. He is also a graduate from Alexander W. Dreyfoos Jr. School of the Arts where he majored in theater. His primary research interests include police innovation and culture, environmental criminology, and situational crime prevention. In his off hours, Justin enjoys exercising, watching classic films, and spending time with his family.