What Is the Right to Repair?

By Elizabeth Chamberlain, iFixit

When you buy something, you should have the right to repair it, whether that means taking it to the repair shop of your choice or fixing it yourself. Manufacturers of all kinds of things—smartphones, tractors, wheelchairs, and beyond—unfairly limit their customers’ repair options, making repair more expensive and difficult.

The Right to Repair movement is a broad international effort to secure our repair options and prevent repair limitations. Right to Repair laws have three main goals: preserving the right to open your stuff, increasing the availability of the parts and tools you need, and keeping independent repair shops in business.

In case you missed it, New York just passed the first-ever broad electronics Right to Repair bill. Next year, New Yorkers will have access to parts, software, and repair documentation for all kinds of electronics. Right to Repair advocates think all people everywhere should have the same access.

It wasn’t so long ago that every cell phone battery could be replaced by hand—without tools—and every appliance came with schematics. But before we realized it, planned obsolescence strategies became the norm.

Companies are against the Right to Repair for one simple reason: Controlling repair makes them money. They profit when you use their dealer repair services. They profit when independent repair shops can’t get the parts to fix your stuff. And they profit when you decide to buy something new because you’re too frustrated by the hassle of fixing what you’ve already got.

Manufacturers will say they’re trying to protect customer safety, even though repair is six times safer than the average job and independent repair technicians come from the same trained, experienced labor pool as manufacturers’ technicians. They’ll say they’re trying to protect customer data, even though the US Federal Trade Commission’s investigation found nothing to suggest independent repair shops are any less trustworthy or careful. They’ll say they care about device security, even though cybersecurity experts from the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins have found “no cybersecurity risk in third-party repair.” Sounds like maybe, just maybe, they’re only preventing repair because they want to.

If you work for a manufacturer, we’re happy to help you figure out how to make your products more repair-friendly.

Shady Anti-Repair Strategies

Here are some of the sneaky anti-repair strategies that manufacturers use to keep you under their thumb and buying new.

Restricting Access to Parts, Tools, and Manuals

Many manufacturers restrict access to parts and tools, refusing to make them available to anyone but their own dealers’ repair shops. This kind of control creates a repair monopoly, locking independent shops out of repairs and enabling manufacturers to set artificially high prices. It’s not a coincidence that a smartphone screen repair is often about half the cost of a new device. The so-called “50% rule” is an arbitrary (but often-cited) point at which many customers will opt to replace instead of repair. In addition to controlling parts, most manufacturers refuse to publish the related instructions—instructions they have already created for their internal use. Withholding repair documentation makes DIY repairs more difficult and more dangerous.

Blocking and Locking Third-Party Parts

Some manufacturers go even further than restricting access to original parts and actually block third-party options. HP was caught using fake error messages to obstruct third-party ink cartridges; HP then paid out a hefty settlement to its printer customers. Apple discourages third-party parts with “unable to verify” warnings that show up as persistent messages on your lock screen and get added to your device information. John Deere puts their tractors into a slow-drive “limp mode” when some errors show up until those errors are cleared by dealer-only software. These disingenuous alerts and artificial feature limitations erode trust in independent repair, driving customers back into the manufacturer repair monopoly.

Pairing Parts to the Motherboard

An increasingly common and awfully effective strategy to block repairs is pairing parts to the device’s motherboard. If a faulty part is replaced with a new one, the main board will refuse to accept it. The only way to replace that faulty component is to find a new part paired to a new motherboard, which makes repair more expensive and complex. We first saw this in the Xbox 360, which “married” the game disc drive to the motherboard, driving up the cost of a disc drive repair by 10 times. More and more manufacturers have started using this strategy to block independent repair. Apple’s Self Repair program locks parts to a device serial number, which dramatically limits the potential for independent repair and end-of-life refurbishment. Manufacturers generally have the ability to re-code these parts to accept new ones. Their own authorized repair shops use pairing software to do so. But keeping that pairing software secret is another way to maintain a monopoly on repair.

Designing Unrepairable Products

Manufacturers make all kinds of unrepairable design decisions that block or discourage repairs. They use proprietary screwheads, so people have to special order the tools they need. Batteries get glued in with industrial adhesive, making basic maintenance ridiculously difficult. Components get soldered together into ungainly assemblies, meaning you have to replace, for instance, an entire top case just to replace a key on a keyboard.

Types of Right to Repair Laws

To fix all of this, we’re fighting for the Right to Repair around the world, in several different categories of legislation.

Parts, Tools, and Documentation Access Laws

The first modern Right to Repair law was the 2012 Motor Vehicle Owners’ Right to Repair Act in Massachusetts, which guarantees car owners’ right to have their vehicles serviced at a shop of their choice. After the law passed, vehicle manufacturers came to the table to negotiate with repair advocates, and in 2014, they finalized a memorandum of understanding that would secure the right for all motor vehicle owners in the United States to access parts, tools, and documentation for their vehicles.

Most of the proposed Right to Repair laws in the United States since then—including the bill that passed in New York—have been based on that model. Right to Repair laws have been proposed in 38 of the 50 US states, most of them aiming to secure owners’ and independent shops’ access to parts, tools, and documentation. Some bills have focused on specific categories of devices; Colorado recently passed a bill securing the Right to Repair powered wheelchairs.

Bills asking for parts, tools, and documentation are currently being considered at the US federal level, addressing electronics and tractors.

Repairability Labeling Laws

We’ve been rating electronics’ repairability for a long time, encouraging consumers to pay more attention to whether the things they buy are repairable. Legislators have taken a cue from these calls.

In 2021, France began to require repairability score labels at the point of sale for five categories of products, including consumer electronics. An OpinionWay study commissioned by Samsung found that by the middle of 2021, the vast majority of French consumers had heard of the index and said they were using it to purchase more-repairable products. An electronic products labeling law was introduced in Washington State in 2022 but did not pass.

French device makers must display these scores at the point of sale.

Just as EnergyStar ratings inform customers of lifetime energy cost, consumers have the right to know how feasible repair will be. Like EnergyStar ratings, France’s repairability rating system helps consumers take tertiary device costs into account and encourages positive, sustainable innovation.

Copyright Laws

On the other end of the fight, many anti-repair strategies are made possible by an overreach of copyright law. In the US, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 made it illegal to “circumvent technological protection measures”—which means that anyone getting around software lock or part pairing strategies, even for the sake of repair, was breaking copyright law. Though the Library of Congress has granted individual repair exemptions to the law, those exemptions don’t cover distributing the software tools you need to activate a new part. In 2022, US Congress began to consider a permanent fix for the abuse of this copyright law. Canada has similar copyright legislation, and in 2021, Member of Parliament Bryan May proposed a law to fight it.

Copyright is meant to protect works from unauthorized duplication. Blocking repair is far outside the intended scope of intellectual property law. Manufacturers have mostly fought repair by arguing that giving consumers access to software locks would result in piracy. But the Register of Copyrights rejected that argument, saying that these concerns “have not been substantiated.” Fixing the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s repair-preventing measures wouldn’t make piracy legal. Companies could continue to prosecute illegal copying of their works. In a Fordham Law Review article, law professors Leah Chan Grinvald and Ofer Tur-Sinai argued that “intellectual property laws should not prevent a right to repair from being fully implemented.”

People who make creative works should be able to make money from them. But using copyright law to prevent repair is a distortion of its purpose.

Product Design Laws

As of yet, laws that require more-repairable designs have not been introduced, but they’re on the way. The European Parliament voted in favor of requiring user-replaceable batteries, in February 2022. Though there are still several steps between this vote and established regulation, European Union member countries will likely pass laws requiring user-replaceable batteries in products sold within their borders.

The Future Is Repairable

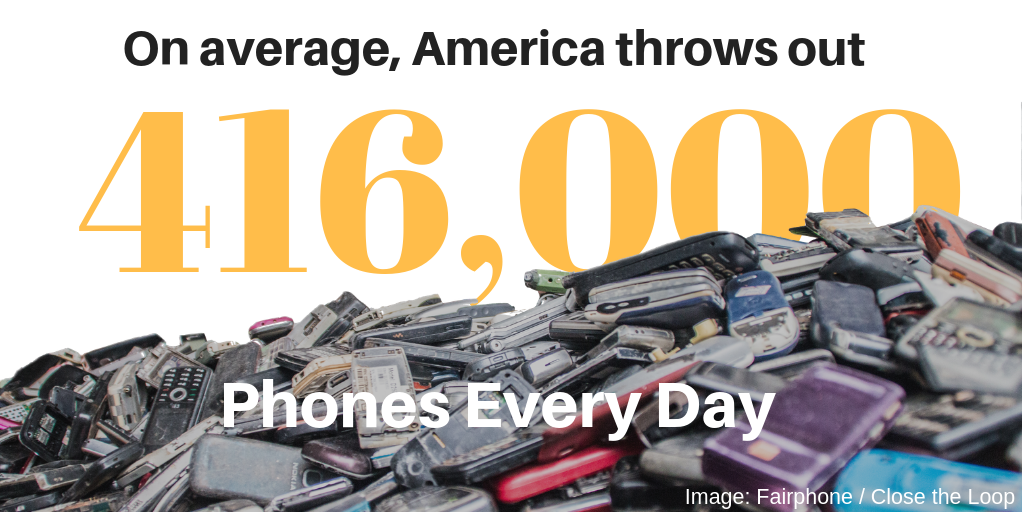

Repair saves people money, helps protect the environment, and teaches people how their stuff works. As a global society, we can’t afford to keep making as much stuff as we are, and we definitely can’t keep throwing this much of it away.

A legally protected Right to Repair will help us get our stuff fixed at reasonable prices. It will bolster jobs and healthy competition. It will expand our ability to choose more repairable things. The right to repair is the future, and it just makes sense.

Want to join the fight? In the US, see The Repair Association. In Europe, Repair.eu. In Canada, CanRepair. In Australia, The Australian Repair Network.

Elizabeth Chamberlain