Mountains of Inventory Create a Slippery Slope for Retailers: Secondary Markets and Other Value Recovery Methods Ebb and Flow

By Stephen Shaw, Inmar

Nearly every retailer was blinded by the blizzard of change kicked off during the pandemic. It started out innocently enough. For many of us, online shopping became more than consumerism. It was a pastime — a welcome interruption from the doldrums of lockdown. And when packages arrived, we were overjoyed. In addition to new merchandise, the delivery reminded us that we were still connected to something beyond the confines of our homes.

Online merchants, many offering free returns, eagerly filled our orders. Bracketed purchases became commonplace, but no one seemed to care. E-commerce was setting new records and shoppers were thrilled that their bedrooms had been transformed into virtual dressing rooms. Working from home fueled the growth of online sales for household-related goods like leisurewear, home décor, small appliances, toys, gardening items, and consumables. It all seemed like a win-win.

Then came the first few flakes of the blizzard — in the shape of random supply chain issues. Retailers, particularly those with a physical presence, saw aisles and aisles of empty shelves. Similarly, online merchants feared the inability to fill orders. Seeing the storm forming ahead, retailers quickly increased order size and frequency to avoid out-of-stocks.

The storm intensified as supply chain issues became the norm rather than the exception. Getting products was easing, but determining delivery dates was near impossible, as ports were clogged with stagnant cargo ships waiting days — even months — to unload their freight. This uncertainty caused retailers to order even more and made demand-signaling systems less relevant. These systems use historical data and predictive analytics to align supply with demand, optimizing the amount, mix and placement of inventories. But retail became unstable, and unstable systems aren’t predictable. The only constant? Retailers need products to sell. Having inventory to sell meant survival, so every merchant’s north star was to secure goods.

Then COVID restrictions subsided, and orders began coming through. Warehouses filled and container-based storage units began popping up to manage the influx of goods retailers so desperately needed. It appeared the storm was breaking, and retailers were no longer operating in the dark. Pandemic fears diminished, and consumerism was poised to help restore the economy — but now inventory was a problem for a different reason.

Consumers, no longer under lockdown, didn’t want leisurewear. Many were returning to work, so they wanted work clothes. The same was true for other categories, particularly those that were so popular during the height of the pandemic. This left retailers with warehouses full of products no longer in demand. But the economy remained strong, and consumers continued buying at unprecedented rates. So much so, inflation crept in — then snowballed. According to the US Bureau of Labor and Statistics, the annual inflation rate for the 12 months that ended in August 2022 was 8.3 percent. This past June, inflation broke a 40-year record by reaching 9.1 percent.

Now retailers are overloaded with inventory and watching it sit as their shoppers’ disposable incomes shrink, with no end in sight. Adding darkness to the blizzard is the upcoming holiday season. Retailers need to stock up because cash-squeezed consumers want to start their holiday shopping early to spread it over a longer buying period. A recent Inmar survey revealed that nearly 73 percent of consumers planned to start their holiday shopping in September and October.

New Challenges for Selling into Secondary Markets

Most retailers began offering deep discounts to help speed the sale of excess goods and make room for holiday inventory. In addition to heavy promotions, retailers often sell excess inventory to liquidators, who in turn sell the highly discounted merchandise into secondary markets like flea markets, bodegas, mom-and-pop stores and out-of-market geographies. But after carrying the inventory so long and offering deep, deep discounts at retail, even if sold into secondary markets there’s hardly any margin left.

Many large retailers have adopted new strategies for liquidating goods at retail without diluting their brand. Dick’s Sporting Goods, for example, has opened more than 40 physical stores called Dick’s Sporting Goods Warehouse Sale Stores. These stores only sell in-store and offer discounts as high as 70 percent. Their traditional stores also offer last chance clearance items that can be purchased in-store or online. This type of self-liquidation will continue to dampen the impact of selling into secondary markets.

These new sales strategies and tactics, combined with deep discounts from major retailers, have softened secondary market demand by 34 percent, according to Curtis Greve, Inmar Vice President of Operations and Remarketing. Greve also said, “The average value of a truckload of excess goods being liquidated is down about 30 percent because of the impact of inflation on shoppers who purchase low-end items. These consumers have to choose between buying non-essential items or gas and food.”

However, as big box retailers realign their inventories, these deep discounts will dissipate and demand in secondary markets will be restored.

A Bright Future for Niche Secondary Markets

Clothing resale is often considered a liquidated segment or viewed as a secondary market. According to Glamour, it’s the fastest growing segment of the fashion industry. In fact, they expect it to double to $77 billion within 5 years. Consumers focusing on sustainability and the circular economy are driving unprecedented growth. Similarly, McKinsey and Company expect 10-15 percent annual growth for the next decade.

Case in point — Helpsy, a Certified B Corporation, is seeing strong demand for returns, overstock, and post-consumer used clothing. Helpsy collects 50 tons of clothes per day from brands, returns aggregators, secondhand stores and consumers. Helpsy sorts and channels these clothes to domestic and overseas thrift stores in bulk. They also sell select items directly to consumers on Helpsy Shop and to the reseller community via Helpsy Source. Despite many retailers’ overstocked inventories, consumer preferences are clearly shifting toward the sustainability of secondhand, as evidenced by Helpsy’s sales growth of 60 percent in 2022.

Refurbished Goods Will Grow as Inventory Levels Normalize

Inflation is likely to push more consumers toward refurbished goods. However, mountains of new inventory sitting in warehouses, marketed with aggressive promotional offers, may dilute the value offered from these goods. For example, a Microsoft Surface Pro 5 is offered for $444.99 refurbished versus $479 new. Some consumers may feel the $34 (a 7 percent discount) doesn’t justify buying refurbished. Other consumers may feel they’re getting a newly refurbished device with the same warranty as a new one, so why waste $34?

But as inventory levels normalize and inflation continues, the price gap between new and refurbished goods is likely to widen. Several large retailers see refurbished goods as another sales channel for reaching different consumer segments without jeopardizing their core brand. Amazon now has Amazon Renewed. Walmart recently introduced Walmart Restored. eBay offers eBay Refurbished, and Best Buy has 20 outlet stores selling open box, returns, clearance and refurbished items.

Then there’s Back Market, a marketplace selling exclusively refurbished electronics — or “renewed electronics” in Back Market jargon. And according to TechCrunch, the company is doing phenomenally well considering the $5.7 billion valuation for the refurbished device marketplace, announced earlier this year.

Refurbished Goods Reach Beyond Electronics and Appliances

When thinking about refurbished products, most of us default to tech and appliances. But inflation — combined with the buying power of Millennials and Gen Xers and a growing concern for the planet — is creating new opportunities for refurbished merchandise. Red Wing shoes, for example, offers sameold.redwingshoes.com. In 2021, Nike offered Nike Refurbished and Timberland partnered with ReCircled, a company that facilitates the transition from a linear to circular model for the world’s foremost luxury brands. Environmental and economic pressures are likely to drive sustained growth and innovation within the refurbished goods segment.

Fighting for the Right to Repair

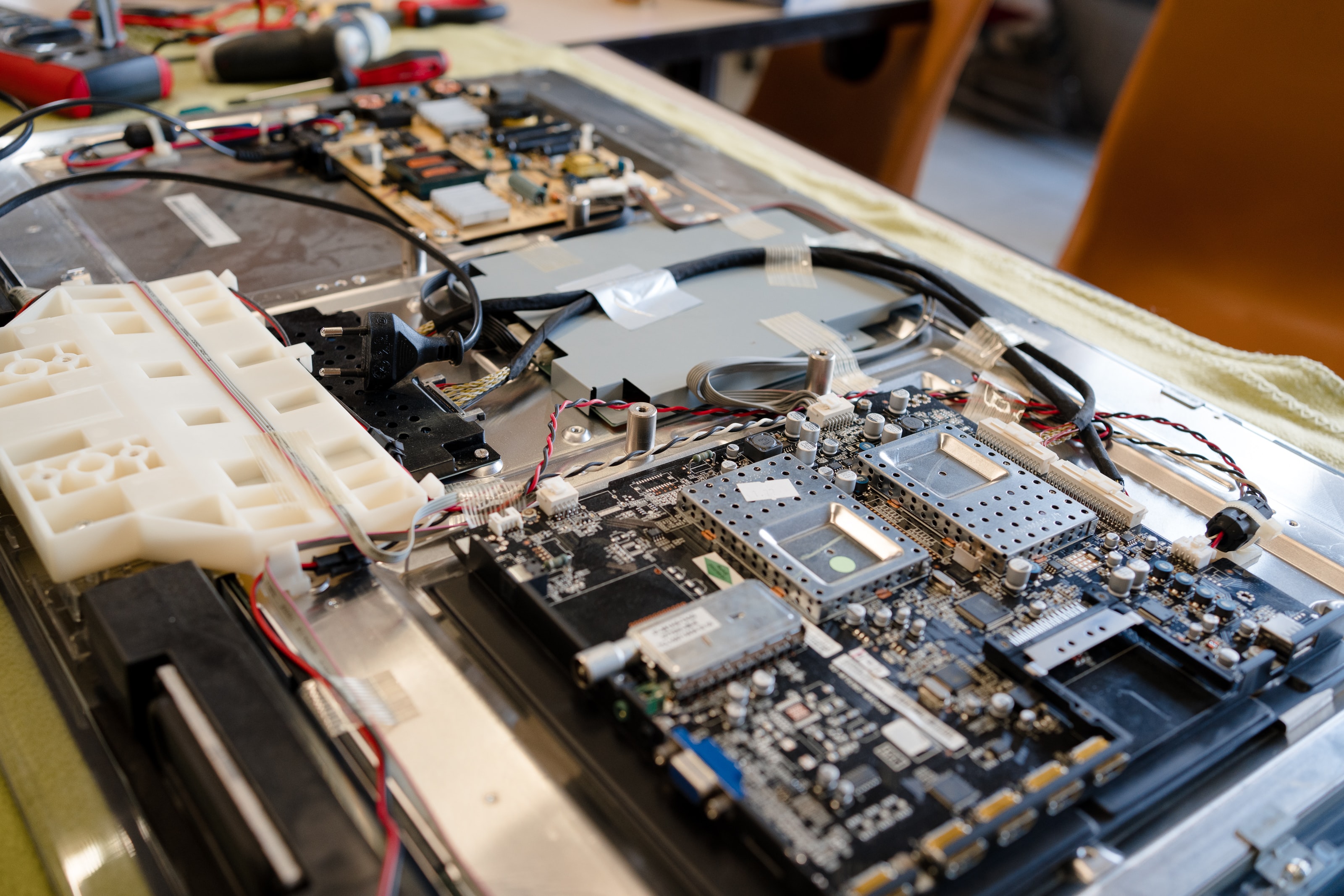

Repairs are an essential part of a true circular economy. But how many of us can repair a laptop? Most of us can’t even extract the SIM card from our smartphone. And many believe that’s by design — similar to planned obsolescence, which was introduced as a manufacturing strategy in the 1920s.

Intentionally avoiding the planned obsolescence debate, the fact remains that most consumers aren’t equipped to perform low-level repairs, especially for today’s highly complex gadgets. But repair has become a point of contention for many. So much so, legislation has been put forth to empower consumers with the right information and tools to repair their own devices.

The Right to Repair movement is more advanced in many European countries and in Australia, but the US is gaining momentum. According to repair.org, 17 states have Right to Repair bills in place. Another 20 states have introduced some form of Right to Repair bill that requires original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to provide consumers and independent repair businesses equal access to repair documentation, diagnostics, tools, service parts and firmware as their direct or authorized repair providers.

Patagonia, for example, a Certified B Corporation, provides a solid model for consumer repairs and even provides DIY guides and videos.

How these Trends will Impact Reverse Logistics

On the surface, you’d think these activities would dilute revenues for many reverse logistics providers. In the short term, this may be true as retailers increase discount rates to move stagnant inventory. This may erode margins, but it’ll also likely force retailers to shore-up their reverse logistics processes to improve value recovery. This, combined with the need to operate more sustainably, will increase the number of returns processed versus being sent to landfills for final disposition. These improved practices will provide even greater value when inventory levels return to normal, which is likely to occur within the next 3-6 months. Reverse logistics providers will get another boost as refurbished goods and resale create expanded opportunities by serving as additional, or extended, sales channels. So while retailers have had a rough few years, constantly adapting and evolving in order to survive a changing market, those who come out the other side will be able to carry the more efficient and sustainable practices they took on into a more settled market — this time to thrive.

Stephen Shaw

Stephen ShawStephen Shaw is Director of Liquidation at Inmar, SupplyTech Division. Mr. Shaw, with more than 12-years’ experience, has become a recognized leader in reverse logistics and remarketing. He holds an MBA from the University of Florida and an undergraduate degree in Finance from the University of Georgia.