Developing a Common Framework for Teaching Supply Chain Management: Why Are We Not Teaching Reverse Logistics?

By Joe Walden, University of Kansas

A recent study into the teaching of supply chain management at the introductory level was completed by comparing syllabi for introductory supply chain management courses to the job announcements for entry level supply chain management jobs. The study started with a data base of 400 syllabi and was narrowed down to 78 that met the criteria of introductory courses. These syllabi were compared to 140 job announcements from the major online job sites over a period of five months to determine if what is being taught matches what is being asked for by industry. As an Academic Member of RLA, one of my concerns in the study was the frequency (or lack of frequency) of reverse logistics as a topic of discussion in the classroom.

The study was originally organized to look primarily at introductory supply chain management courses (the focus was expanded in 2018 to look at all SCM classes) with a focus on:

a) What is being taught in the supply chain courses?

b) What text book is being used to teach these

courses?

c) How do the curriculums align with corporate

The goal of the three prong approach was to determine if we are teaching what the students need to know in order to set the conditions for success in the job search and in the corporate world upon graduation?

The study included a detailed analysis of what the Gartner “Top 25 Supply Chain Undergraduate Programs” (2018) and the US News and World Report Top Supply Chain Schools (2018) are teaching in their introductory supply chain management courses compared to the Supply Chain Management programs that were not listed in the Gartner Research Top 25 Programs or the US News Rankings. One of the impetuses for this study was comments from several recruiters that what was being taught in some schools “was not what was needed in the real world.” Some of the leading schools in the Gartner and US News and World Report rankings are providing students with an education that is resulting in up to six job offers per student. Is there a correlation between what we are teaching and what industry is asking for? Does this lead to more opportunities for the graduates from the top programs? Does this lead to better quality graduates entering our work force? Does the data indicate that we may be harming the students’ professionally by not teaching what industry wants?

Is there any background research on this topic? The research started with a detailed literature review focused on supply chain education, supply chain curriculum development and the growing supply chain management talent gap. The literature review revealed:

• The literature and trade magazines confirm the reality of the talent gap based on growing skill requirements (MHI, 2015; Ackerman, 2016; Ryder, 2017), growth in the supply chain industry (Harrington, 2015; Stevens, 2017) and a shortfall in the quality of what is being taught in university programs (Gravier & Farris, 2008; Maloni, Scherrer, Campbell, & Boyd, 2016).

• The review of literature concerning supply chain management talent and supply chain management curriculums to meet the needs of the talent shortage reveals that while there has been a great deal written about supply chain management, there has been very little focus on the topic of supply chain management curriculum development. Jordan and Bak (2016) confirmed this in their review of 24 studies over 15-year period. Their research led them to the conclusion that there is a need for future research into supply chain management curriculums. This was confirmed by Birou, Lutz and Zsidisin (2016) when they reported “There are relatively few studies which have been focused on SCM (supply chain management) curriculum” (p. 73).

• The literature review reveals several concerns within academia and industry about supply chain management education and the quality of the education process for students applying for jobs. There are concerns about what is taught, what is not taught, what should be taught, how supply chain management is taught and how often classroom materials are updated, if ever. This research project only focused on what is being taught and what should be taught.

• Research points to the gap between industry needs regarding competencies within supply chain management and the acquired competencies/skills/knowledge sets of baccalaureate graduates (Wong, et al., 2001; Birou and Lutz 2013; Birou, et al., 2016).

• The APICS (APICS is now the Association for Supply Chain Management) Basics of Supply Chain Management Exam Book (2016) contains a list of four hundred and forty-nine key terms approved by industry as critical for understanding supply chain management and required understanding for taking the Basics of Supply Chain Management exam as part of the APICS certification process. This list of terms served as the foundation for the first coding of the syllabi and job announcements. In addition, the Gartner Top 25 Supply Chain Schools (Gartner, 2018) identifies supply chain competencies and leading and trailing programs based upon curriculum and industry recruiting practices. The Gartner report has a high level of credibility with industry leaders, as they are part of the research survey respondents. The study looked at the topics taught by the Top 25 Schools for 2018 and the US News and World Report top ranked schools, as well as other non-Top 25 schools that teach supply chain management.

• The APICS Certified in Production and Inventory Management Exam Bulletin lists words that are considered Operations Management terms. This listing helped identify topics covered in SCM classes that were actually operations management topics. The purpose for looking for operations management terms was based on claims by Alakin, Haung, and Willems (2016) that some supply chain management courses were actually operations management courses that had their titles churses that had their titles changed to supply chain management without changing the curriculum or topics covered.

• In Pedogogy of the Oppressed, Freire points out that educators have to continually reflect on the field of study and ensure that they are not harming the student by not teaching current materials that challenge the students to think critically (1970). This supports the question of what are we teaching and why?

Study background: Over a period of three years syllabi were collected from schools around the world for supply chain management classes. Currently this data base contains over 400 syllabi. The focus of the original study was to compare the written curriculums for introductory supply chain management courses; this study was expanded in 2018 to also include higher level supply chain management courses. The rationale or basic assumption for this start point was that the introductory course should provide a foundation for supply chain management majors for follow on courses and at the same time provide all business majors with an understanding of supply chain management and the relationship of supply chain management to other business disciplines. Another basic assumption built into the analysis was that what was reflected in a syllabus as the written curriculum matched what was actually taught in the classroom. This second assumption may or may not be a completely valid assumption.

The syllabi were collected through a variety of sampling techniques. Some were captured through a simple online search for “supply chain management syllabus,” a note was sent to colleagues in the supply chain management education field asking for submission of supply chain management syllabi, this resulted in snowball sampling as some colleagues forwarding the message to other colleagues resulting in a snowball effect sampling. Other syllabi were captured through convenience sampling and the final data capture technique involved a search of CourseHero.com for “supply chain management syllabus.”

Over the course of the fall 2017 major college/university recruiting season, seven different data captures for job announcements were conducted to establish a sample data base for what industry was asking for in their recruiting process. The search criteria was for “introductory supply chain management” positions using the major search engines of Indeed.com, Careerbuilder.com, Monster.com and JobsinLogistics.com. These websites were chosen based on the popularity of the sites and the number of job announcements reflecting introductory supply chain management jobs. While several hundred job announcements fit the criteria of the search, the data capture used a simple random sampling technique by selecting every fifth job announcement from each of the websites during each data capture session. The duplicate announcements were discarded. Jobs that required specific industry experience such as “aviation supply chain experience” and jobs that specified a master’s degree were also eliminated to keep the data set of introductory supply chain management jobs. This produced a database of one hundred and forty job announcements across a five month time frame in the Summer/Fall of 2017.

Methodology: The study was a mixed methods approach to analyzing the syllabi and the job announcements that employed both qualitative and quantitative approaches.

The syllabi were coded first for key words from the APICS Basics of Supply Chain Management certification handbook and the APICS Body of Knowledge. From these key words a frequency distribution was created. The syllabi were analyzed for all of the 78 introductory supply chain syllabi as a whole and separating out the Top Schools (Gartner and US News) compared to the non-Top programs to see if there was a difference in what was reported as being taught.

The job announcements were coded similarly to the syllabi in respect to coding for key words from the APICS Certification Handbooks and APICS Body of Knowledge. This produced a frequency distribution for both what was reflected as desirable in the job announcements and the actual frequency of how often the terms were used in the job announcements.

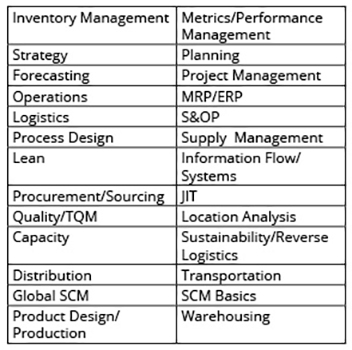

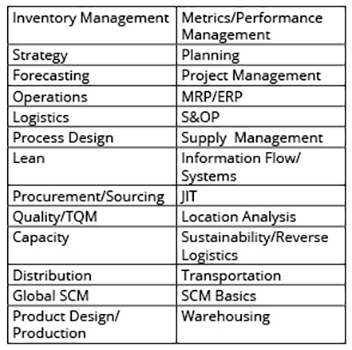

Analysis: The frequency distributions for the syllabi were compared to the frequency distributions for the job announcements. Table 1 shows the top topics that were reflected in the syllabi. While Table 2 shows the top requested topics in the job announcements.

Table 1: Most Frequently Taught Subjects/Topics

from the Syllabi

Table 2: Most Frequently Requested Topics

from the Job Announcements

The goal of the analysis was to determine if there was a difference between what industry wants and what academia is teaching. Further analysis was conducted to determine if there was a significant difference between what was being taught compared to the job announcements at the Top Schools compared to what was being taught at the non-Top Schools. There was also a thematic analysis and coding performed that linked common terms such as environment and sustainability or purchasing and contracting to help link the syllabi topics with the job announcement topics. The thematic analysis linked common topics that appeared in the APICS Dictionary under “see also…” This thematic analysis was added to the research to provide a different lens analysis and link common topics.

What the analysis showed was that the Top Schools were more closely aligned with the needs of industry. There was a 71.7% match between the topics of the top schools to the job announcement topics. However, when using a thematic analysis to link associated topics, the top schools match of what was being taught compared to what was being asked for by industry rose to 88.7%. When looking at the schools that were not listed in the Top Schools listings, the match was much lower at 41.5% after the thematic analysis and comparison.

The results of the analysis and comparison would indicate that the Top Schools are better meeting the needs of industry in educating their students. A further step in the analysis to try determine if we are teaching what industry needs was to look at the top 25 topics in the syllabi for all of the schools compared to the top 25 topics in the job announcements from a correlation perspective.

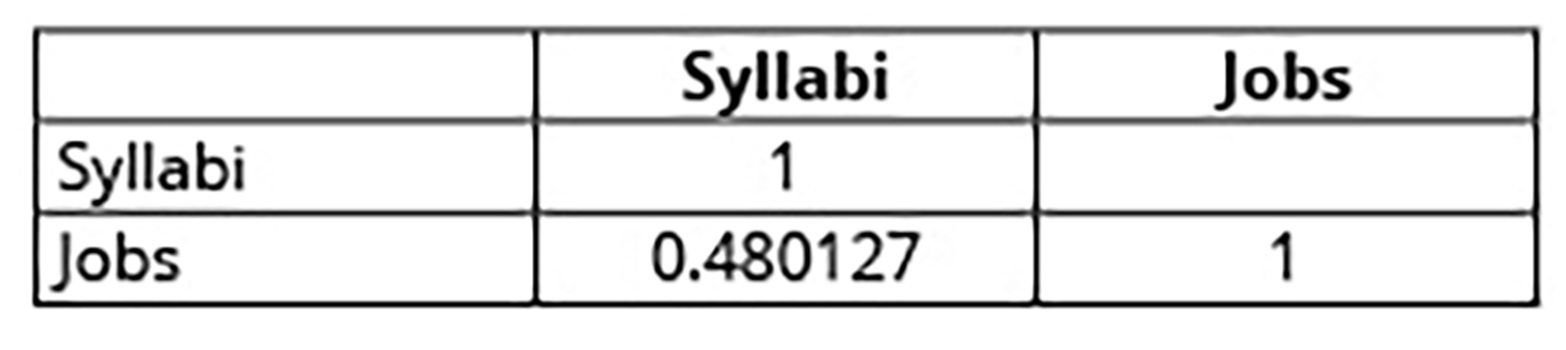

While there is no assumed causation between what is represented in the syllabi and the key topics in the job announcements, there is a correlation coefficient of 0.48 between the top thirty topics in the job announcements and the top thirty topics in the syllabi as shown in Table 3 below. The correlation coefficient was calculated using the frequency of the topics mention in the syllabi compared to the frequency of the topics mention in the job announcements. A coefficient of 0.48 does not indicate a strong relationship between the syllabi terms and the job announcement terms. A correlation between the topics that is this low would seem to point to a large gap between what is being asked for in the job announcements and what is being taught according to the syllabi in the introductory supply chain management courses.

Table 3: Non-Top 25 Schools Correlation between Taught Topics and Industry Needs

Reverse Logistics Implications

Not only are we not teaching, in most classes, the necessary topics of supply chain management to meet the needs of industry and prepare our students for success but, of greater concern from the reverse logistics perspective, the analysis of the 400 plus syllabi revealed that only seven, or only 1.75%, of the courses represented in the syllabus data base reflected reverse logistics as a topic.

What does all of this mean? The research and analysis of introductory supply chain management courses when compared to the job announcements for introductory supply chain management jobs shows that as a whole, universities are not doing a good job of preparing their students to be successful in the job market which may be a factor in the large talent gap that industry is facing. From a reverse logistics perspective, the concern is even greater. Academia is not exposing the students to the concerns of reverse logistics, the link between reverse logistics and sustainability or the value proposition for the company from reverse logistics.

Is this a problem? It is a very big problem, as the Reverse Logistics Association moves to RLA 2.0, one of our responsibilities as educators is to introduce our students to the concepts of reverse logistics. As practitioners and Third Party Providers, we need to actively engage our local colleges and universities to help them implement reverse logistics into the business and supply chain management curriculums.

By linking and comparing what industry is asking for in their job announcements to what is being taught in the classroom, we can better prepare our students for what they will see in commercial world upon graduation. The closer the curriculum is to the needs of the customers (in this case the companies recruiting our graduates), the more competitive the students will be in the recruiting process.

The Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) Model is one of the foundations of the analysis in Gartner ranking analysis. The SCOR Model contains six functions that are inherent in every supply chain: Plan, Source, Make, Deliver, Return, and Enable. With the announcement at the 2019 Reverse Logistics Conference that the RLA is teaming with the Association for Supply Chain Management (ASCM is the owner of the SCOR model) to produce a reverse logistics certification program, it is even more important than ever before to link academia and industry to get reverse logistics practices and principles into the classroom. Linking academia and the reverse logistics industry will provide a win-win for academia, industry and the students coming out of business schools entering our workforce.

References

Ackerman, K. (2016, February 10). The Crisis in Talent Management. Retrieved February 10, 2016, from DC Velocity: http://www.dcvelocity.com/print/article/20160208-the-crisis-in-talent-management/ Akalin, G., Huang, Z., & Willems, J. (2016). Is Supply Chain Management Replacing Operations Management in the Business School Core Curriculum. Operations and Supply Chain Management, 9(2), 119-130. Retrieved November 1, 2016

APICS. (2016). Basics of Supply Chain Management Exam Manual. Chicago: APICS. Birou, L., Lutz, H., & Zsidisin, G. (2016). Current state of the art and science: a survey of purchasing and supply chain management courses and teaching approaches. International Journal of Procurement Management, 9(1), 71-85. Retrieved June 13, 2017

Blackstone, J. H. (2013). APICS Dictionary, 14th ed. . Chicago, IL: APICS.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed (30th Anniversary Edition). New York: Bloomsbury.

Gartner. (2018, June). Gartner recognizes top university programs. Retrieved July 24, 2018, from Gartner: https://www.gartner.com/en/supply-chain/trends/supply-chain-university-top-25 Gartner Research . (2016). Top 25 Supply Chain Schools Undergraduate. Boston: Gartner Research Center.

Gravier, M. J., & Farris, M. T. (2008). An analysis of logistics pedgogical literature. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 19(2), 233-253. Harrington, L. (2015). Solving the talent crisis. Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland.

Johnson, & Pyke. (2000). A Framework for Teaching Supply Chain Management. Journal of Production and Operations Management, 9(1). Retrieved Nov 1, 2015

Jordan, C., & Bak, O. (2016). The growing sale an scope of the supply chain: a reflection on supply chain graduate skills. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 21(5), 610-626. Retrieved October 24, 2016

Maloni, M. J., Scherrer, C. R., Campbell, S. M., & Boyd, E. (2016). Attracting Students to the Field of Logistics,. Transportation Journal, 55(4), 420-442. Retrieved July 1, 2017, from http://muse.jhu.edu/article/633851/pdf

MHI. (2014). US Roadmap for Material and Logistics. Charlotte, NC: MHI.

MHI. (2015). 2015 MHI Annual Industry Report. Charlotte, NC: MHI.

Ryder. (2017). Best Practices for New Supply Chain Talent Strategies. Ryder System, Inc. Retrieved July 20, 2017

Stevens, L. (2017, July 27). Help Wanted: Amazon to host job fair for 50,000 postiions amid hiring squeeze. Retrieved from The Wall Street Journal: https://wwwlwsj.com.articles/help-wanted-amazon-to-host-job-fair-for-50,000-postions-amid-hiring-squeeze

US News. (2018). Best Undergraduate Supply Chain Management / Logistics Programs. Retrieved August 2018, from US News and World Report: https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/rankings/business-supply-chain-management-logistics

Joe Walden

Joe WaldenJoe Walden has 40+ years in warehousing, distribution, operations and supply chain management. A new text book on supply chain management and operations management was released this summer. In addition to operational supply chain experience, Joe also teaches graduate and undergraduate classes in Operations Management for the University of Kansas. https://business.ku.edu/joe-walden