Back to School on Competitive Bidding Methods

By Kate Vitasek, University of Tennessee

Logistics organizations generally think of procurement as a “make vs. buy” transaction. This was especially the case as organizations began to explore outsourcing.

Many assume if they “buy,” they should use competitive “market forces” to ensure they are getting the best possible deal. This is evident in companies where logistics professionals earn bonuses for achieving year-over-year cost savings.

As organizations seek the best price, the default approach is to use a transaction-based model where a buying organization can “test the market” by comparing prices across transactions–such as price per hour, per widget, per mile, per kilogram, etc.

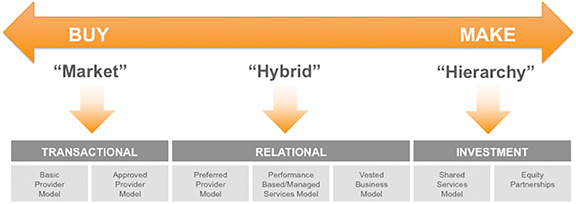

But the transactional approach is not very efficient in larger, complex and/or strategic situations. Too many procurement organizations use conventional “buy-sell” transaction-based competitive bidding approaches for buying complex and strategic outsourcing deals. That’s why logistics professionals should consider sourcing solutions along a continuum of possible options, as illustrated in Figure 1, Sourcing Business Models on the Sourcing Continuum:

Leaders in reverse logistics outsourcing have shown that highly collaborative win-win relationships can yield significant value for the buying organization and the supplier. Forward-thinking organizations such as Intel and Dell are starting to shift their sourcing efforts to strategic, performance-based and “Vested” outcome-based supplier solutions (see the December 2018 issue for more information on the Dell and Intel case studies https://rla.org/magazine/article/view?id=1001).

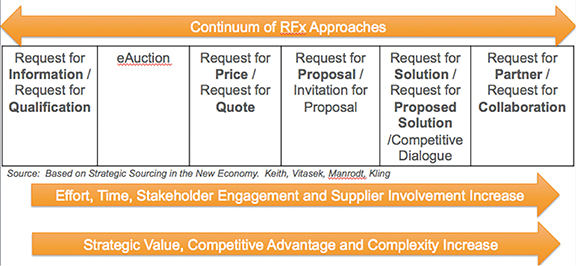

As organizations shift to more complex Sourcing Business Models, it follows that they should use more sophisticated and collaborative bidding (RFx) approaches that buy “solutions,” “strategic partnerships” or “alliances.”

Thus organizations need more collaborative types of approaches designed to help buyers and suppliers evaluate “solutions”—not just based on a supplier’s bid price for a standard commodity or logistics service specification.

Figure 2: Continuum of RFx Approaches

Note: Request for Tender is a common government procurement term that is often associated with the private sector terms Request for Price or Request for Proposal.

Each of the RFx approaches is summarized below. The University of Tennessee has a comprehensive white paper – “Unpacking Competitive Bidding Methods: The Essential ABCs of the Various RFX Methods,” which can be downloaded from the Vested library.

1. Request for Information (RFI; also referred to as a Request for Qualification) — used to obtain general information about products, services or suppliers. An RFI is sometimes used to gather benchmark information and general data from the marketplace. Buyers rarely if ever pick a supplier based on RFI information and in many organizations, are actually prohibited from doing so. Rather, they use the information to help them further refine their RFx approach. As such, an RFI typically precedes other RFx processes and often is used to help buyers create bid lists. An RFI can be used with any of the RFx processes, but it is almost always used with a request for proposed solution and a request for partner process. An RFI is not binding for either buyer or supplier. They range from simple requests aimed at gathering market intelligence to more comprehensive requests asking suppliers to answer detailed questions about their qualifications.

2. Electronic auction (e-auction) — an online, price-centric auction where purchasers specify what they are interested in buying and prospective suppliers respond by entering competing bids. Often suppliers are pre-qualified to participate in an e-auction so that Terms & Conditions, SOWs, and SLAs are comparable and buyers can focus almost exclusively on price. There are various types of e-auctions including a reverse auction where a single buyer uses a fixed-duration bidding event in which multiple prequalified and invited suppliers compete for business. A seller-driven e-auction is an electronic, online auction where suppliers post items for sale and buyers bid on the items.

3. Request for Price (also referred to as a Request for Quote) – used to obtain price offers for a specified product or service. A request for price is used for more standard sourcing initiatives where cost consideration is the key decision criteria. Buyers using a request for price must properly define the requirements, often through a pre-established contract, so there is no ambiguity for the supplier or buyer. A quotation may or may not be a legal binding offer.

4. Request for Proposal (also referred to as an Invitation for Proposal) — used to obtain pricing as well as detailed descriptions of services, methodologies, program management, cost basis, quality assurance, and other support provided by the supplier. Requests for proposals are used for larger, more complex and technical sourcing initiatives when supplier selection is based on factors beyond just price or cost, such as technical capability or capacity. Technical (e.g., SOW, SLAs, security, process maturity), Financial (e.g., price, budget, TCO impact), and Terms & Conditions (e.g., compliance/risk evaluations), Strategic Alignment (e.g., cultural compatibility, corporate social responsibility values), and other factors often play a role in award decisions. A request for proposal allows a buyer to specify requirements and allows suppliers to define some of the “how.” For example, a buyer may ask a supplier to outline how it proposes to manage quality. The Request for Proposal is a primary way the organizations conduct competitive bid situations for outsourcing initiatives.

5. Request for Solution (RFS; also known as Request for Proposed Solution) — an emerging competitive bidding methodology popularized by the outsourcing advisory firm ISG and later promoted by Gartner. The request for solution methodology uses a more open approach in which a buying organization has a dialogue with potential suppliers with the intent of collaborating to determine the best solution to meet the buyer’s needs. An RFS is different than an RFP because the buyer does not know the optimal solution. And it is different than an RFI— if a satisfactory deal can be achieved, the buyer is ready to buy, not just down-select and launch an RFP. In an RFS, the buyer asks bidders to propose the most appropriate solution bound by any critical constraints (e.g., scope, scale, interoperability with existing solutions, security requirements). The buyer gives limited direction that is primarily focused on the existing environment and what the success criteria may be. Then, the buyer requests the suppliers involved to design a solution to best meet its business needs. Because requirements are not mandated, bidders differentiate on how much value and innovation they bring to the table.

6. Request for Partner Request for Partner is a term coined by University of Tennessee researchers to describe a highly collaborative competitive bidding process used for strategic and complex sourcing initiatives. A Request for Partner process uses some of the key concepts found in the various request for solution methodologies, but formalizes them into an “open source” methodology. A key goal is to identify a supplier that is innovative and able to provide transformation through outsourcing, and also is a good “fit” for the organization. For this reason, the competitive bid process is very transparent and encourages collaboration – all the way from developing requirements through contract development and established governance mechanisms the parties will use after the contract signing. The highly collaborative methodology allows the buyer and supplier to not only develop the “solution” during the bidding process, but also to establish a working knowledge of how well the organizations work together.

Another important aspect of the Request for Partner process is the ability to select the supplier with a good “cultural fit.” Organizations that are using a Request for Partner process are doing so because they want to create a highly strategic, long-term relationship – often purposefully created to drive transformation or innovation. Purposely picking a supplier with a strong cultural compatibility is an essential difference to a more “classic” way of sourcing.

The Request for Partner methodology is well-suited when a buying organization needs to develop a long-term contract with a strategic supplier for a highly complex and strategic outsourcing initiative. It is also ideal when the buying organization is seeking a supplier who will play a major role in transformation or innovation. The process is designed for use by buyers and suppliers seeking high degrees of collaboration, cultural fit and a “what’s in it for we” mindset.

Conclusion

As organizations mature and their approaches to sourcing reverse logistics become more sophisticated, there is a need to turn to more collaborative Sourcing Business Models such as Performance Based or Vested models. But doing so requires a shift to incorporate more collaborative approaches into the competitive bidding process as well.

Instilling collaboration into the bidding process enables buyers to work with suppliers to find both “solutions” and potential “partners,” not just on providing a “price” for a specification.

The Request for Solution and Request for Partner methodologies offer a promising approach that enables buyers to tap into the creativity and innovation of potential suppliers while still allowing for a competitive environment. The process allows suppliers to create better solutions that are purpose-built for adding value and driving innovation.

To learn more about the Request for Partner process - download the University of Tennessee’s white paper at Vested Library.

Kate Vitasek

Kate VitasekKate Vitasek is an international authority for her award-winning research and the Vested business model for highly collaborative relationships. She is the author of six books on the Vested model and a faculty member at the University of Tennessee. She has been lauded by World Trade Magazine as one of the “Fabulous 50+1” most influential people impacting global commerce.