There’s a “dark pattern” that’s emerging in the smart electronics space: manufacturers that sell pricey, connected products are arbitrarily declaring their products “obsolete” and “dead,” then passing the news along to their customers—who don’t agree.

We’ve saw this play out with the Sonos speakers back in 2019 when the company that sells pricey, wireless home audio devices introduced a program to have customers “brick” functioning speakers and send them to a e-cycling center in order to qualify for a discount on upgraded hardware. That led to a massive backlash, with customers pointing out that sending perfectly functioning hardware to the landfill was about the least sustainable thing imaginable. That saw Sonos reverse course, enabling customers to qualify for the upgrade without disabling their existing speaker.

And it’s what happened more recently with the music streaming service Spotify. That company’s first experiment in hardware, the Car Thing, allowed owners of older model cars to use Spotify in their vehicles. It launched in 2021. Within a year, however, Spotify declared that it was discontinuing sales of the Car Things after considerable losses. Then, in May, 2024, it informed customers that it was ending support of the device, closing down the cloud based services that Car Thing relies on and essentially bricking all the devices in service.As with Sonos, Spotify’s recommendation to customers was to “dispos[e] of your device following local electronic waste guidelines,” placing the burden of the corporate decision squarely on their customers, and not to mention the planet! As PIRG’s Lucas Gutterman pointed out in a blog post this week, Spotify, Sonos, and other firms have a choice about how to handle these “end of life decisions.” Among other things, firms like “Spotify should make tools available for consumers so they can keep using the devices,” he wrote.

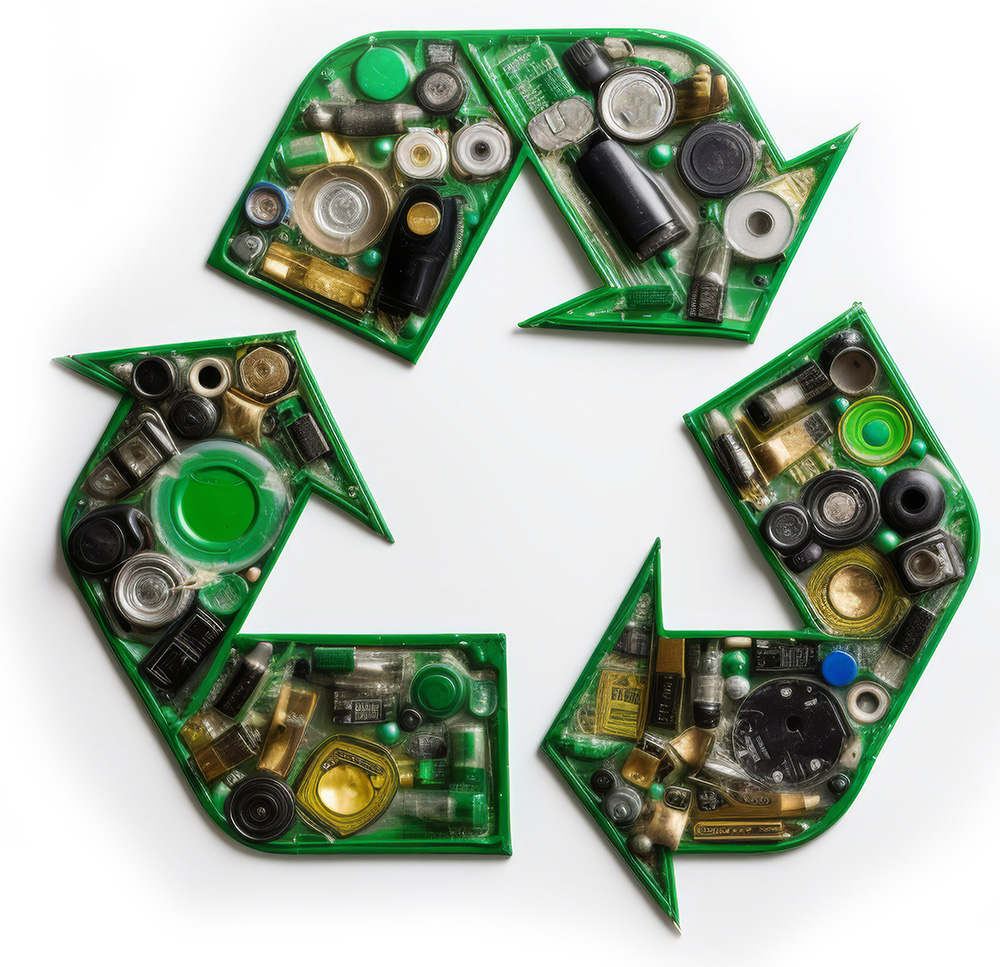

Alas, there’s little evidence of such a change happening. Consumers in the United States collectively dispose of more than 500 pounds of electronic waste each second, with e-waste one of the fastest growing forms of pollution. However, as it stands, there is little disincentive for manufacturers to continue to brick and abandon products they no longer with to support. No laws or regulations govern arbitrary decisions to cut off support and effectively kill off functioning hardware. And in most states, the cost and onus for disposing of manufacturer-abandoned smart devices falls entirely to consumers and local communities, rather than the manufacturers who designed, built, marketed and sold the devices.

That simmering crisis may take on entirely new dimensions next year, when Microsoft ends support for its Windows 10 operating system—a business decision that could condemn more than 200 million electronic devices to the landfill. What’s needed are guardrails for manufacturers and software makers – guidelines around both the creation and long term management of smart, connected devices that takes not only their corporate bottom line and “shareholder value” into consideration, but also the rights of consumers, the useful life of hardware and the environment.